Where There’s Smoke

Published November 1, 2024

My brother and I are fast asleep on the coast of southern Oregon while a light layer of ash collects on his Vanagon, muddling the burnt orange paint and getting caught in the fibers of his canvas pop-up. I spot the tiny white flecks floating around earlier that night, but had it not been for the dingy tint of light scattered around our campsite, they’d have likely drifted along unnoticed. This shade of destruction is distinctly dark, almost like taking the golden glow of any other evening and mixing it up with the black soot that’s to be left behind by this one. If you didn’t know any better, you’d see how it paints the world and think it was beautiful. That night, bundled in fleece for the first time in months, I almost do.

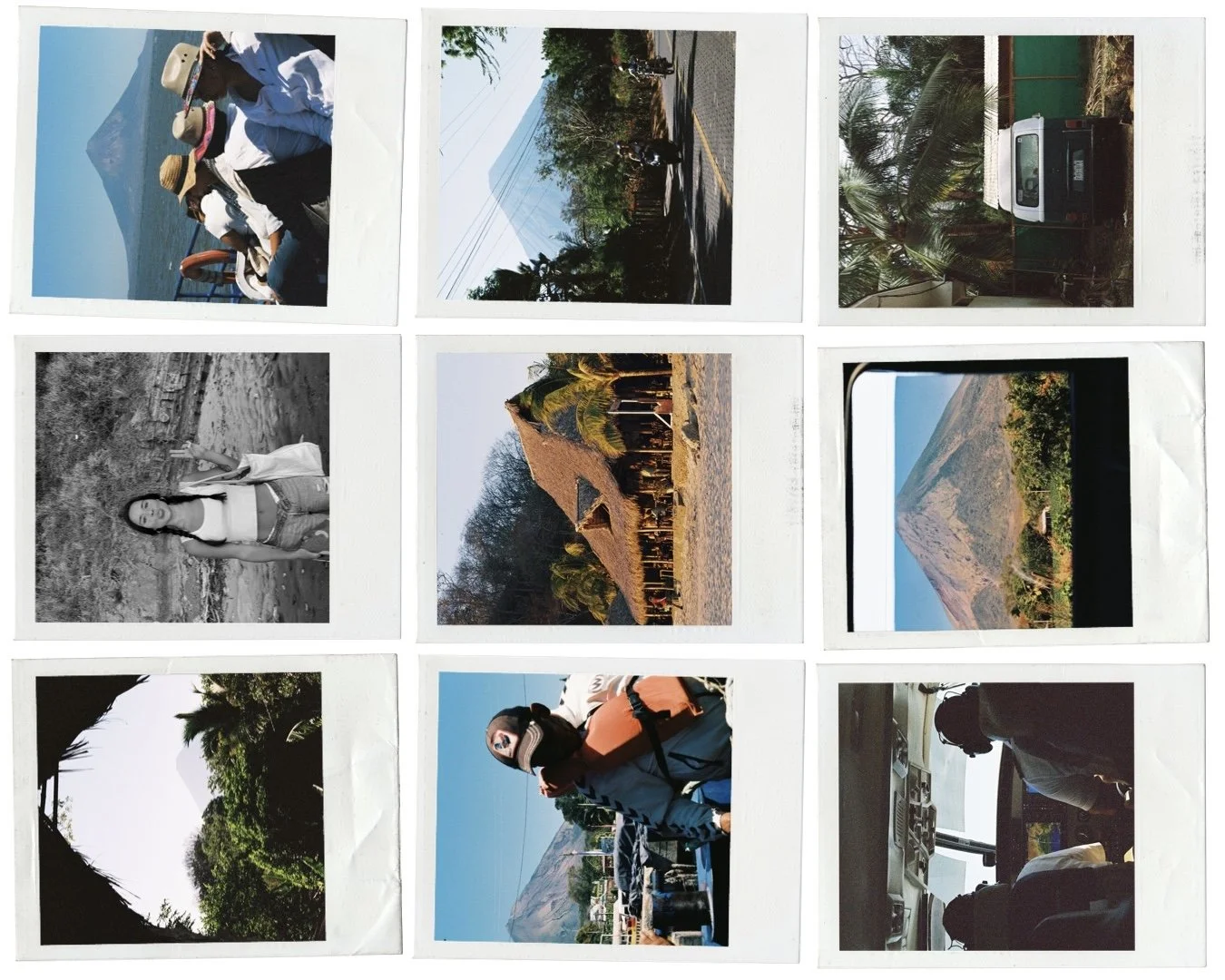

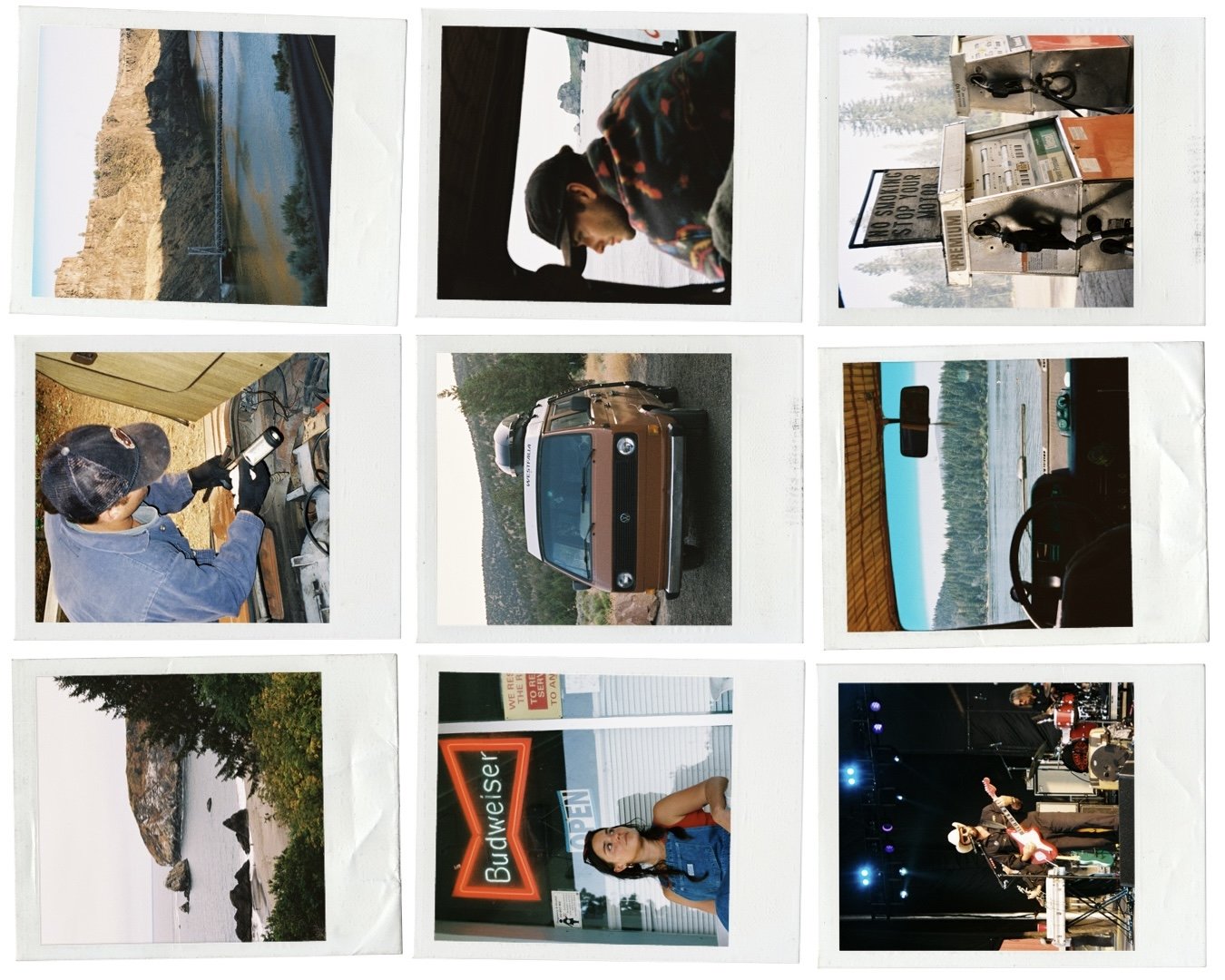

It’s the middle of July 2024. California is experiencing its hottest summer on record and thousands of fires have already burned hundreds of thousands of acres across the West Coast. Owen and I set off on a week-long road trip from Sacramento, California to Bend, Oregon, and back in the thick of it all because we have to — our journey is planned around a music festival the coming weekend. That’s to say, we didn’t choose the timing, the timing chose us, and it almost kept us from going at all. Like people, the van can only stand so much heat before it starts to break down. And like wildfire season, you know that overdue maintenance will lead to something bad, but you don’t necessarily know how bad it will get. But like both of those things, it’ll often only take a handful of tools, a little bit of hope, and a lot of determination to mend and move forward. And that ignorant sense of optimism is how we find ourselves on the first leg of the trip, driving down CA-20 on a triple-digit day without any AC, sweating our asses off by mid-morning. We spend hours under miles and miles of unbroken blue sky looking out at miles and miles of dry landscape and I think, “If God reached out and touched these hills, she’d pull away with a blister.”

It’s somewhere around Clearlake Oaks, about 103 miles in, that Owen pulls off the road and into a gas station. We’ve overheated. I watch all 40 liters of our water bleed out across the blacktop as he digs around in the engine. We sit tight for over an hour feeling the air heat up and wondering how this hunk of metal could ever cool down. But eventually, it does, and we carry on further north towards cooler temperatures. On fuel and snack stops, I scroll through my feeds and see friends from all over the state posting about fires near them — the Lake Fire, the Lost Hills Fire — and offering well wishes and resources to those around them. I think back on all of the years I watched a blanket of flames barrel toward places I call home. At that moment, shirt sticking to my back and an unquenchable feeling of thirst, I’m grateful not to be them. And that next evening on the chilly coast, dragging my hand along our picnic table to create clean lines left behind by dirty fingertips, I think I’m just playing with the remains of far-off fires that trailed after us with the wind. I think we’re slowly putting distance between us, these disasters, and the worst of the heat. This very well may have been the case, but while we’re tucked tight into our sleeping bags that night, thousands of lightning bolts are striking vulnerable ground all over Oregon.

Growing up on the West Coast means wildfire season is unofficially cemented into your calendar. You know that July and August are almost predestined to burn. Winter’s snowpack isn’t just about an epic ski season, it also helps determine how much anxiety you’ll start to feel as those months roll around. A lack of rain brings back memories of the years you lived through drought, monitoring every drop of water that came out of every faucet. Back when Owen and I were kids, swim meets would be called off due to dangerous air quality and camping trips would get canceled for being too close to burn paths. In the summer of 2021, two of my close friends were getting married in Lake Tahoe. The bride and I sat at my living room table on the first night of her bachelorette party, just the two of us, because the smoke from the now infamous Caldor Fire was so thick we couldn’t see out of the windows, which meant pilots couldn’t see out of theirs either. Friends and family couldn’t fly in for the ceremony and their reception was moved indoors to a nearby ski lodge. When all was said and done, that fire claimed 221,775 acres in the Sierra Nevada. It destroyed 1,005 structures, damaged 81, forced 20,000 people out of their homes, and caused immeasurable damage to surrounding ecosystems. These events aren’t always easy to cope with, but for us, they’ve always been part of life. At that wedding, we double-fisted bottomless free beer thanks to everyone who couldn’t partake in the open-bar cocktail hour and shouted lyrics to our favorite songs loud enough for them to echo off the A-frame ceiling. We knew the fragility of what surrounded us and we found gratitude for the things still standing. It wasn’t until I experienced a wildfire on the East Coast that I realized how abnormal this reality is.

In the summer of 2023, Canada saw its worst wildfire season to date. All that smoke blew right down to New York City, where I’d been living at the time. My friends who had grown up out there had never seen anything like it. They looked around in awe of the smokey streets and couldn’t believe how unfazed I seemed by it. My social media feeds were filled with photos of a hazy sun with the caption, “Thanks Canada.” No one seemed concerned with what was going on with our neighbors to the north — what they were losing, what precedent this level of disaster could set for years to come, or what it was telling us about climate change. The day the AQI was at its worst, I sat inside a coffee shop and watched people take drags of cigarettes at sidewalk tables as the air got visibly thicker. Those couple of days were a novelty for them. The smoke cleared up and wildfires became even more of a reason most people would never move West.

But for a lot of us who have never known a world without it, living through drought and wildfire is a small price to pay. The glistening rivers, the giant pines, the rocky coastlines, and the high deserts are well worth the fear of what may come in those summer months and the risks these natural disasters may pose to ourselves and what’s around us. We live for what we have, we love it fiercely, and we strive to protect it in the ways we can.

The morning we leave the coast, Owen and I head 250 miles inland to get to our next camping spot at Diamond Lake directly across from Mount Theilsen. The final stretch of road before arriving is charred. It’s long and straight and lined with black sticks shooting out of the ground that fan out for hundreds of yards in what was once called a forest. When the mountain finally comes into view, its sharp peak is hidden by what appears to be a cloud. As we get closer, we realize that cloud is originating from the mountain itself, and a quick Google search confirms that last night, lightning struck its surface, setting it ablaze and resulting in level 2 and 3 evacuations.

We assume our site will be enveloped in smoke and too dangerous to camp in, or that if we aren’t technically forced to leave, we’ll need to make that decision ourselves. I’m trying to come up with our next move as we pull in, but the ground is clear and campers are carrying on as usual. The sites are right on the water, and looking across, we see the wind is blowing all of the smoke in the opposite direction. At night, airtankers fly overhead and we can smell the difference between the small contained fire in front of us and the uncontrolled one across the lake. The sky above is clear enough to see stars. We walk back to the shore to get our eyes on what’s taking place less than three miles away. The mountain is unrecognizable — a blinding source of neon light in place of what should be the landscape’s deepest contrast. We watch the fire rage as we sit silently on our side of the water, where the trees are still green and the critters still swim around in the shallow and laughter swirls through the crystal air behind us, and we feel lucky.