The Nicaragua Journal.

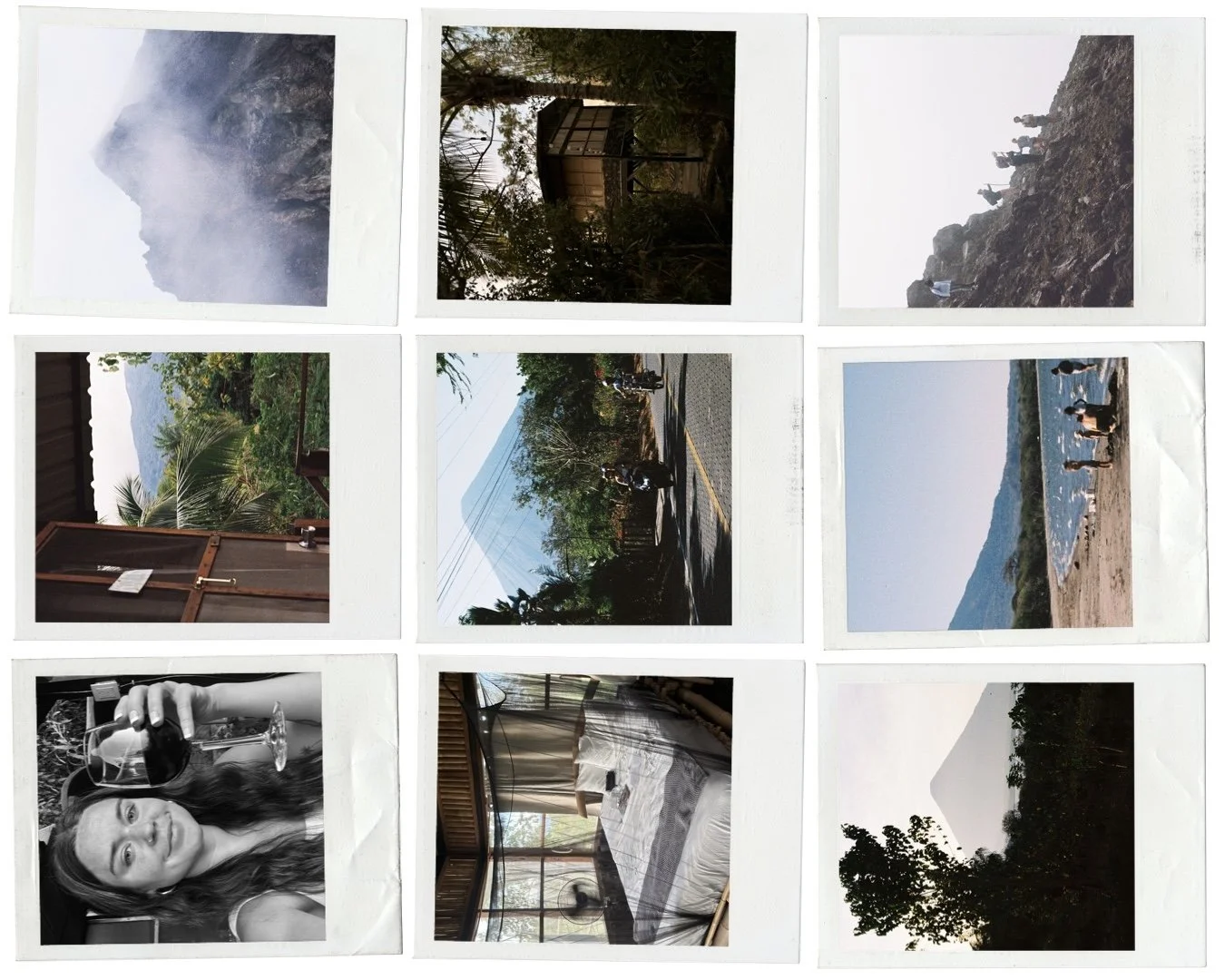

Chapter III: La Espiral

Published April 15, 2024

My driver, Mayner, is twenty minutes early to pick me up. No rush, he says, but I’m throwing my toiletry bag in my duffel and sprawling out on the floor to make sure all of my belongings are where they belong, anyway. It’s my final day in Playa Maderas, I’ve just come back from a morning well spent at a café that Maria recommended I try, and I’m buzzing from an excess amount of espresso. The car is here to take me to the ferry, which will take me to Isla de Ometepe, my most anticipated leg of the trip. It’s an island in the middle of Lake Nicaragua formed around two volcanos, Concepción and Maderas. Unlike San Juan Del Sur, Playa Maderas, and my final destination of Popoyo, it's full of recreation beyond lying on a beach or lying on a board. There are hikes up either volcano, natural pools, waterfalls, kayak tours, windsurfing lessons, and farm-to-table restaurants serving from a harvest that takes place right on the island. For the first time since I landed three days ago, anticipation is unmistakably winning in the battle against anxiety.

When I slide into the back seat of his car, Mayner warns me of the bumpy ride ahead and spends the first half hour or so avoiding potholes and checking in on my well-being. It’s just under two hours to San Jorge Port and the view is comparable to everything else I’ve passed by: dry fields that go on for miles, partially built, unmarked structures, trash tumbling along the side of the dusty road. We pass one or two manicured resorts that leave me feeling unsettled and wishing they weren’t there.

Before we get to the large gate that gives way to the port, Mayner lays out exactly what’s going to happen. I’ll hand the guard $1 USD, then we’ll go to the ticket counter where I’ll buy my one-way to Ometepe, and then I’ll board the ferry. I assume he’s just making conversation until the gates open up to a massive swarm of cars, trucks, and pedestrians that I’m sure to someone is organized, but to me, is just chaos. A man in uniform bangs on my window and Mayner looks back as if testing me. Everyone here gives me totals in USD, but I only have Córdobas, the local currency, and am forced to calculate how much I owe every time I need to settle up. This makes the whole exchange take longer than it should and I fumble through my wallet before finally handing him cash. At the ticket counter, I approach the window and find a woman behind the glass counting bills who doesn’t acknowledge my presence. Two men who work there are leaning against the wall a few feet away, watching.

“How much?”

She glances up and says something I don’t catch. It’s commonly known that no one who works here speaks English so Mayner steps in to help and a ticket for the noon ferry eventually slides toward me. It’s 11:56 and the boat leaves at the far end of the pier. Having drank a full water bottle on the drive, I ask if there’s a restroom and he tells me to use the one on board. I nod and sprint to catch it before I’m left behind.

On the stern, I push past cars and motorbikes until I enter a room that’s so dark it takes my eyes a solid minute to adjust. I blink a few times and realize it’s full of passengers squeezed side by side on long wooden benches that look like church pews. Backpacks, suitcases, and duffel bags are shoved into every crevice that bodies aren’t, so I push down the aisle, following the light towards an open door on the other side. At the bow, I run into a pile of suitcases next to two giant spools that hold the rope used to dock. The only place left to go is up, toward a narrow balcony full of passengers at the end of an even narrower flight of stairs, so I reluctantly throw my duffel on the ground and get out of the crew’s way.

The second-floor passenger room is just as crowded as the first and when I poke my head in everyone looks up, warning me not to try. Just inside the entryway is the door to the restroom. I open it and find that the toilet has no seat, the water in the bowl is dark brown, and there’s no lock. I decide the pain in my bladder isn’t as bad as the consequences of going in there and I climb the last flight of stairs. At the top, all of the seats are taken, so I stand by the railing for the duration of the hour-long ride and watch the volcanos grow larger on the horizon.

I’ve never been cattle, and I’ve never been herded, but I bet it feels a lot like getting off the Ometepe Ferry. I endure a few shoulder checks before I’m back on land, searching for a man holding a sign with my name who my hostel has sent to pick me up. When I approach him, I find that he doesn’t speak English. Up until now, language hasn’t been much of a barrier. But, after I throw my luggage in his car, I try to ask him if I can find a bathroom before we start our drive to the other side of the island and he gives me a blank stare. I try again by saying, “Baño?” and he nods and points towards what looks like a ticket counter, saying something that I don’t understand. I walk across the parking lot and get stuck in line behind a group of UK backpackers who can’t figure out which shuttle to take. My driver must see how frantic I’m becoming because I watch him cross the parking lot and speak to a few men who then turn to me and speak over each other in Spanish. I’m no more fluent than I was five minutes ago. Eventually, we all give up and the two of us walk back to his car.

Sitting in his backseat in the dirt parking lot, well on my way to getting a UTI, I realize I can’t make it the full hour it will take to get to my hostel. What’s worse, I started my period that morning and am convinced that I’m bleeding all over this poor, unassuming man's cloth seats. With sweat dripping down my shirt and hair sticking to the back of my neck, I pull out my phone to use Google Translate, but this only seems to confuse him further. He says something and pulls his phone out, too, but he can’t get his app to work and refuses to use mine. He continues to speak to me as if I’ll suddenly and miraculously start to understand him and I keep assuring him that I won’t.

We carry on like this in his sweltering car until, having reached my breaking point, I get out and point to the trunk. He shakes his head and points toward the ticket counter. I shake my head and persistently motion towards the back of the car until he finally pops the latch. I unzip the side pocket of my duffel, pull out a tampon, and show it to him. He looks away briefly, as if embarrassed for me, then pulls ten Córdobas out of his wallet and hands it over. I immediately understand it to be the restroom fee. I try to refuse the money but he insists and walks me back to the counter, like father and child. I hand the woman behind the glass the bill and she hands me a ticket along with a wad of toilet paper. I’m ushered around the building to a back alley, where I hand my ticket to a man who lets me through a fence. When I come out, my driver is still standing there waiting for me.

We leave the port town and turn onto the main road that will take us to Balgüe, where I’m staying for the next three nights. Eyes glued to the window, I feel my excitement building the further we go. On either side of the road, hundreds of green palms flick past like I’m watching an old movie projection. No matter where I look I see a volcano, a body of water, or both. By the time we get to Santa Cruz, the town right before mine, we’re driving along the lake’s shoreline, where the Papagayo creates waves that lap against a long stretch of beach. Between the road and the sand are restaurants and cafés donning wooden signs that sway in the breeze and carry their names in vibrant paint.

At least a half-dozen times throughout the journey, my driver pulls to the side of the road, throws his hazards on, and tries to have a conversation with me. Each time, I have to tell him I don’t speak Spanish. Each time, he pulls out his phone and has Google Translate, which is now working, tell me what he wants to say. He shows me where he grew up and where he now owns a house, he asks me how long I’ll be here, or he rolls down his windows and tells me to take photos of various things. “In Nicaragua, we live to serve,” a robotic voice tells me. I take his phone out of his hands and make it say that I think his home is beautiful. This man is perhaps the nicest person I have ever met, and after our fifth or sixth or twentieth attempt at communication, I’ve never been more anxious to get away from someone.

The closer we get to my hostel the further we seem to get from civilization. We’ve slipped back into a monochrome world, made up of colors that look like faded versions of what they used to be. Pale dirt roads, pale dry plants, pale sky, pale hopes. Back in San Juan Del Sur, a few people I’d become friendly with told me of their plans to come to the island for a foam party happening near the port and questioned why I wanted to stay all the way out in Balgüe. I’d stuck with my gut, trusting the reviews and various blogs telling me that, of the entire island, this area was their favorite.

I pay my driver and walk up the path to reception, past construction workers and the giant holes they’re digging, and find a woman at the desk who speaks minimal English. I look around the property and there isn’t another soul in sight. Unlike the other places I’ve been, there’s no town, beach, or other kind of central location that everything is built around. On this island, you choose a place to sleep and figure out the rest from there. I put my things on my assigned bed in an eight-person mixed dorm, then grab my passport and cash when I realize my lock doesn't fit on the lockers. I look up restaurants in the area and find a café that’s about fifteen minutes in the direction I came. Desperate to get back to the landscape I found so comforting, I start walking.

Five minutes down the road, there’s nothing around except locals sitting on dirt bikes and cement blocks. I have no idea where I’m going or what situation I might run into if I keep walking and suddenly, I feel trapped. I think of all the places I want to go and things I want to do and start to imagine a world in which none of it happens. I begin to think I made all of the wrong decisions, I question why I chose to stay in this area, why I chose to come to Ometepe, and why I chose to come to Nicaragua at all instead of a place that’s more tourist-friendly.

The world around me feels like the end of a bad dream. When you start to slowly gain consciousness and recognize that things aren’t right and that this isn’t real, but you haven’t fully woken up yet, so there’s nothing you can do about it. My eyes are threatening to spill over but I refuse to cry in front of an audience. Overwhelmed, I head back to my hostel to catch my breath and potentially find somewhere else to stay that’s closer to anything or anyone.

When I get back to my room there’s a woman around my age who looks vaguely familiar putting her things on the bed below mine. “Did I just see you on the ferry?” I blurt it out, almost like an accusation. It turns out she got here a week ago and there’s someone else on the island walking around with blonde hair, denim shorts, and a striped yellow shirt. We make the appropriate small talk to confirm each other’s sanity before I follow her up a spiral staircase to the common area.

Being in this space feels like being in the treehouse you wanted to build when you were five. A colorful beaded curtain opens up to a wooden coffee table surrounded by tapestry-covered couches built out from the bamboo walls. Beyond that, four hammocks lay side by side, parallel to an A-frame window that presents a view of Concepción. I tuck into a corner of the couch and spend the evening switching back and forth between reading silently and making small talk with Kaitlyn. Night falls and she breaks our latest silence. “I’m gonna go downstairs and get a beer. You want one?”

The near-hysteria from earlier lasted no more than ten minutes, and by the time the bottle hits my mouth, I’m laughing to myself about how silly the whole thing seems. How one moment can make you feel like the world is crashing down, then a few more things unfold and suddenly you’re somewhere else, and everything’s OK. There have been a couple of instances like that on this trip. Situations where the thing that happened in real life was completely different from how it’s portrayed online or how it played out in my head. Warning lights flash because my brain can’t make sense of the uncharted, and being completely alone, I’m solely responsible for navigating it. On a trip like this, where I’m packing up and moving on every day or two, there’s no time to get comfortable. When a place starts to become familiar, it’s already time to change course to a new town with new surroundings, new faces, and new social rules. But that was the point. I didn’t come here to settle in, but I don’t think I realized just how unsettling that would be.