The Nicaragua Journal.

Chapter V: Desolate Paradise

Published April 15, 2024

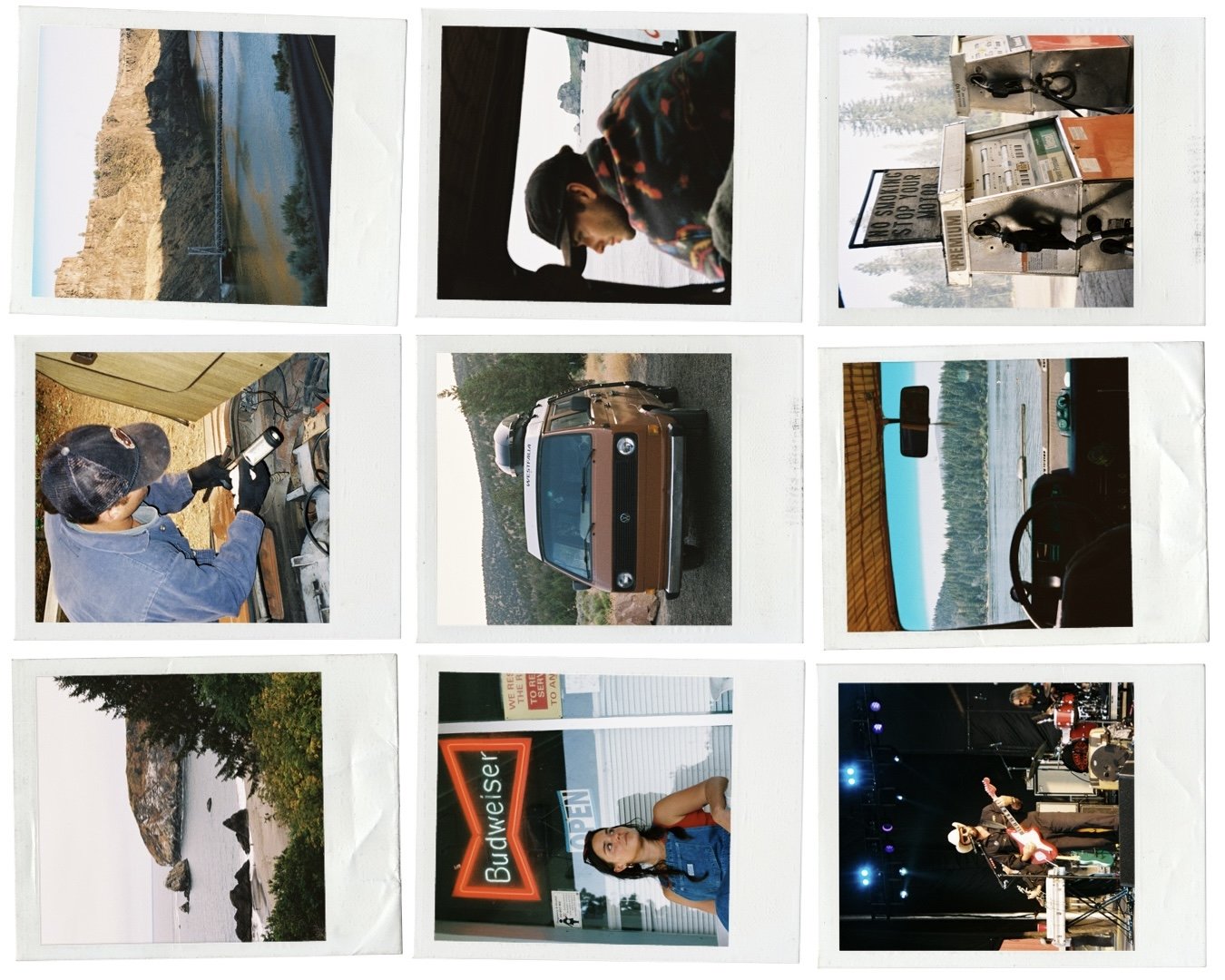

I have a tattoo that symbolizes one of the most impactful realizations of my life in perhaps the most cliché way imaginable. It’s a feather that follows along my ribs, and I got it at the end of my time studying abroad in Australia. The bottom is drawn like any other feather, but on top, the barbs are replaced by mountains starting right at the base of the quill. As you continue down the vane, there’s a van with a surfboard fastened to its roof driving down to where the tip is replaced by waves. Usually, I forget it’s even there, until I’m somewhere like Popoyo, where I’m reminded why I got it in the first place.

For the first two decades of my life, my world encompassed the Sacramento Valley, the Sierra Nevada, and a tiny stretch of the southern California coastline. Living in another hemisphere and traveling all over New Zealand and Southeast Asia during my breaks from Uni Sydney expanded that exponentially and, naturally, expanded my view of the world as well as my place in it. But despite being physically far from where I grew up, I never felt far from home. Often, I would land somewhere totally foreign to me, find the coastline or the edge of a lake or look out at a mountain range, and I’d be comforted by the equanimity of being close to something my soul connects so strongly with.

The feather is a thing that drifts easily and often. The waves, the ocean, and the open road are the things that fill my tank, fully and without fail. They are the promise of stability no matter where I choose to stray. Six years ago I realized the impact of trusting my unrest and going as far as I wanted, because, mileage be damned, I can never truly be far from home. It’s a realization turned into a visual metaphor that I etched into my skin to be as permanent as I am.

Popoyo, a tiny coastal town renowned for and built around its exceptional surfing, feels like home the second my feet hit the ground. This is, in large part, thanks to a handful of influential locals who were here not too long before me.

Recollections are somewhat contradictory, but legend more-or-less has it that León native Arturo Molieri was one of the first, if not the first, Nicaraguan surfer to consistently shred the country’s coast. He worked for Líneas Aéreas de Nicaragua and Pan American Airways and regularly flew from Managua to the United States, where he caught the same bug as all of the coastal counter-culture legends of the 1950s and 1960s. Perhaps the only decent thing the U.S. has ever spread, he brought the stoke back home with him and passed it on to pioneers like Carlos Deshon and Ronald Urroz, who can also take credit for bringing the centuries-old sport to Nicaragua just decades ago.

In the 1970s Deshon went to Central California to attain a master’s degree, then, later, to teach courses at Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo. When he returned home in the 1980s, board in tow, Nicaragua was in the midst of civil unrest and, unable to return to what had become the war-stricken city of León, he spent a year exploring the waters of San Juan Del Sur. Soon after, he and local surfer Filipe Currans took his 4x4 Jeep to Popoyo, where surfing became their escape from brutal conflict and its beaches became their refuge.

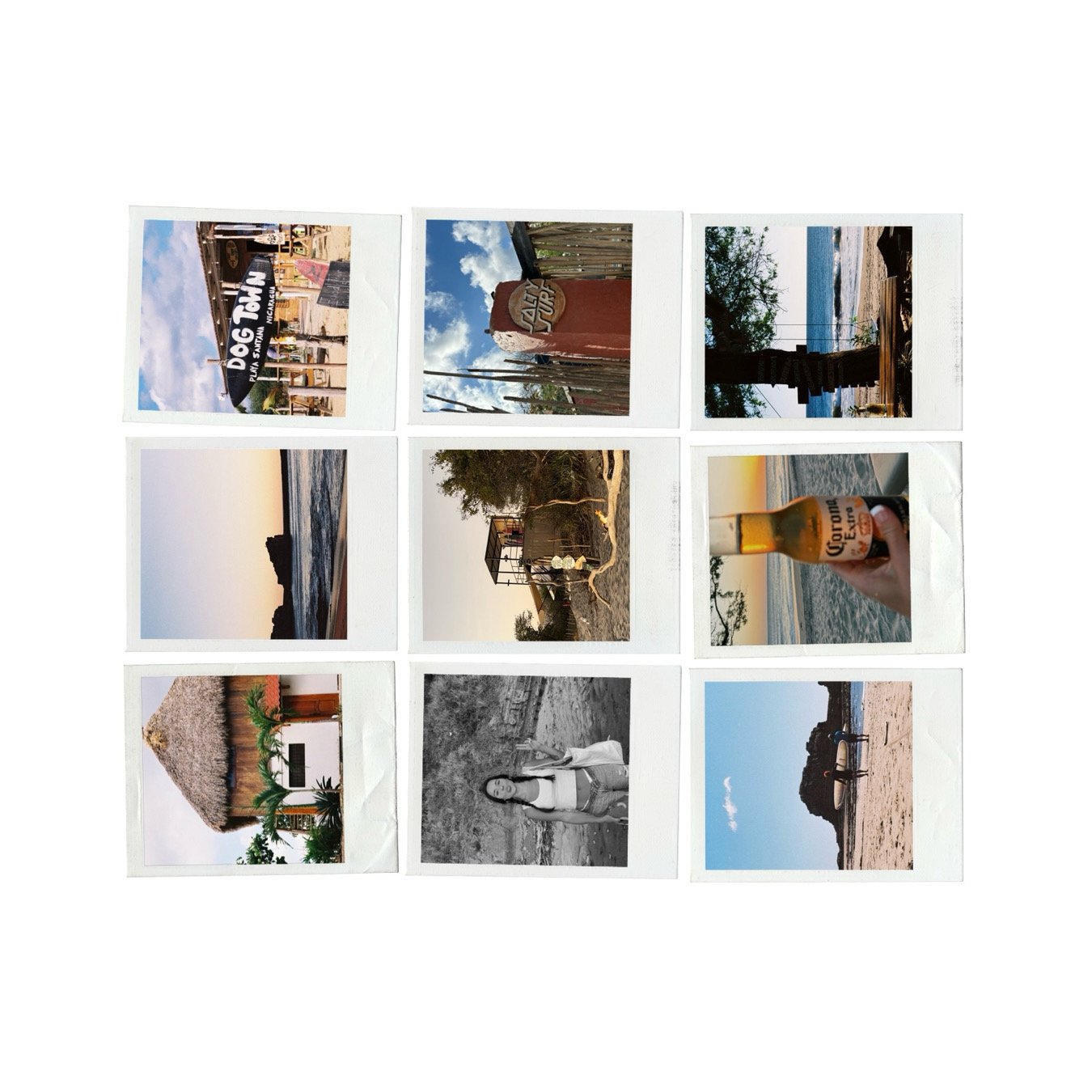

We all owe these men a cold one for the Nicaraguan surf culture that exists today, but we owe them two for the way their spirits are alive in Popoyo. In my hostel, you can feel it everywhere. Half of the entryway is taken up by a rack full of boards that belong to residents. There are three rooms full of bunk beds and one small kitchen with a large, square bar table in the center. We all share one bathroom. One shower, one sink, one toilet. It doesn’t feel claustrophobic, but communal. Everything in here is wet and sandy. It doesn’t feel dirty, but lived in. It’s right on the water and the common area is the beach, which has tables, hammocks, chairs, couches, and a stocked bar. When people are out here, everyone is facing one direction: Out. In a beach town, it’s the water that unites us. The sea is what we all have in common — a source of life that we all live for. It’s one of the most deeply complex, undiscovered, and powerful entities known to us, and it is the very thing that makes life so simple.

Like most places I’ve stayed in or driven through, there’s not a lot going on here. Restaurants and cafés are few and far between. If you turn your head in its full rotation, you’re guaranteed to catch a long stretch of negative space. Run-down shacks pop up every so often along the dirt road and you can never be sure where you’re going unless you’re keeping an eye on Google Maps. If you need something, you go to Ocean Market, where they carry a few groceries and fewer toiletries. It’s also the only place in all of Popoyo where you can get cash in this cash-only town.

If you need coffee, a liquid lifeline that my hostel does not provide, you can go to Dog Town, an establishment that has more hard liquor than caffeine and is also a boutique selling wax, crystal necklaces, a hodgepodge of clothing, and random halves of bikinis. In one corner, there’s a couch that faces a wall covered in photographs and a tapestry that says, “It’s 5 O’clock somewhere!” Below that, Play Station 2 controllers are attached to a TV that shows special features from Tony Hawk’s Pro Skateboarder on loop. They’re playing Orpheus Under the Influence by The Buttertones, a track buried deep in one of my California surf playlists.

The town is a desolate paradise. And the people in it, like the options of places for them to go, are also few and far between. They’re around but rarely seen. They’re off laying in the shade or bobbing in the water, being still, living slowly. I’ve quickly fallen in love with Popoyo for the town that it is, but I love it more for the people it attracts. On my first night, I watch the sunset, then sit and journal while I wait for my food to come out from the bar. In my peripherals, I watch someone who’s swinging in a hammock get up, walk over, and take a seat on the bench across from me. “You journaling?” he asks. This sparks a two-hour conversation between Andre and I. It’s easy. Easy to laugh, easy to shift between surface-level topics to deeper ones, and then back again. Easy to be unaware of how long we’ve been sitting here. He’s from Germany, though he spent a substantial amount of time living in Australia. He loves to surf, but learned on a short board and can’t quite get the hang of anything longer than 6’ 0’’. He smiles often and he chuckles as though it’s as automatic and vital as breathing. He seems to be everyone’s best friend without consciously taking on the role of anyone's best friend.

Later that night, I’m reading on the couch inside, waiting to be tired enough to go to sleep while all three of my roommates, infamously known as “the French girls,” are outside, living up to their reputations at the bar outside with people who aren’t staying here. One of the guys crashing in the room across from me sits in the chair to my right and kicks up his feet for a while. Rick is from Virginia but lives in Boise. He hates the winter and always has. He recently turned thirty-one, which made him feel like all of the things that he’s always wanted to do, but has been putting off, need to happen right now. Being here is one of the things he’s always wanted to do. He also wants to learn origami and carries a kit with him in his suitcase everywhere he goes. He thinks it would be a thoughtful thing to leave someone who’s made a mark on his life throughout his travels, and I think he’s right. He still doesn’t know how to use it.

The next morning, I’m at a table outside, writing some more, when I ask the girl sitting behind me if she can watch my stuff for a sec. My thanks turns into an introduction. Maggie is twenty-four. She’s from Connecticut and is incredibly well-traveled. She’s a writer working remotely while she lives here with her little brother for a month. We become fast friends. After sitting together for a while, she gets up to retrieve a water bottle and a small ceramic cup with a metal straw sticking out. I ask her about it, and she tells me that her family is from Argentina. There’s a Latin American tradition of sharing Mate and in her bottle is a drink called Yerba Mate. She pours some into the mug, sips until it’s gone, refills, then passes it to me. I do the same, and this cycle continues until the bottle is empty. We participate in this ceremony, silently, as two new friends running on fifty-to-one.

The morning after I get back to New York, my roommate pulls out a stool from beneath our kitchen counter and asks, “Did you find yourself?”

I briefly glance up from the grounds I’m pouring into my coffee press and tell her, “I was never lost.”

And I wasn’t. I didn’t go on this trip in pursuit of the self. I know who I am and how I want to live, and that’s ultimately what gets me on the plane despite the ambivalence towards doing something significant for the first time. In the two weeks between booking my ticket and taking off, there are floods of both excitement and terror that take over my whole body, coating my skin like they’re seeping from the inside out. They ebb and flow so frequently that I often don’t know what I’m soaked in, but I know that however agonizing, I can’t let uncertainty be a barricade.

When these nine days are in my rearview, it’s not the frustration of the language barrier, the initial disappointment at some of my run-down hostels, or the stress of getting myself from place to place that I think about. Later, the memories that seemed mundane at the time become a comfort when the city gets overstimulating. Later, I find out that the Papagayo winds touch the Sierra Nevada before they travel down the Nicaragua. Later, the disbelief that I could have ever considered bailing on this trip becomes more intense than the fear I felt before I left.

I didn’t need to find myself, but I was overdue to test my threshold for adventure. I’d been doing so boldly in my career — traveling extensively to be on set, taking on tasks I was in over my head on but then figuring out, leading projects before it was technically my time to lead — and every time, I’d come out on the other side a more capable version of who I was before. After the layoff, I was hungry to explore the limits of all the things I’d been sacrificing to be so dialed into work. To push these limits, to learn lessons, to come out on the other side a more holistically capable version of who I was before.

No matter how you shake it, if you do something even though it’s daunting, then next time, you’ll do something even more far-fetched, and you’ll do it with more confidence, and all of a sudden you’ll have replaced all of your daydreams with tangible memories. And then, when all is said and done, you’ll get the privilege of looking back on your life and knowing that you really lived it.