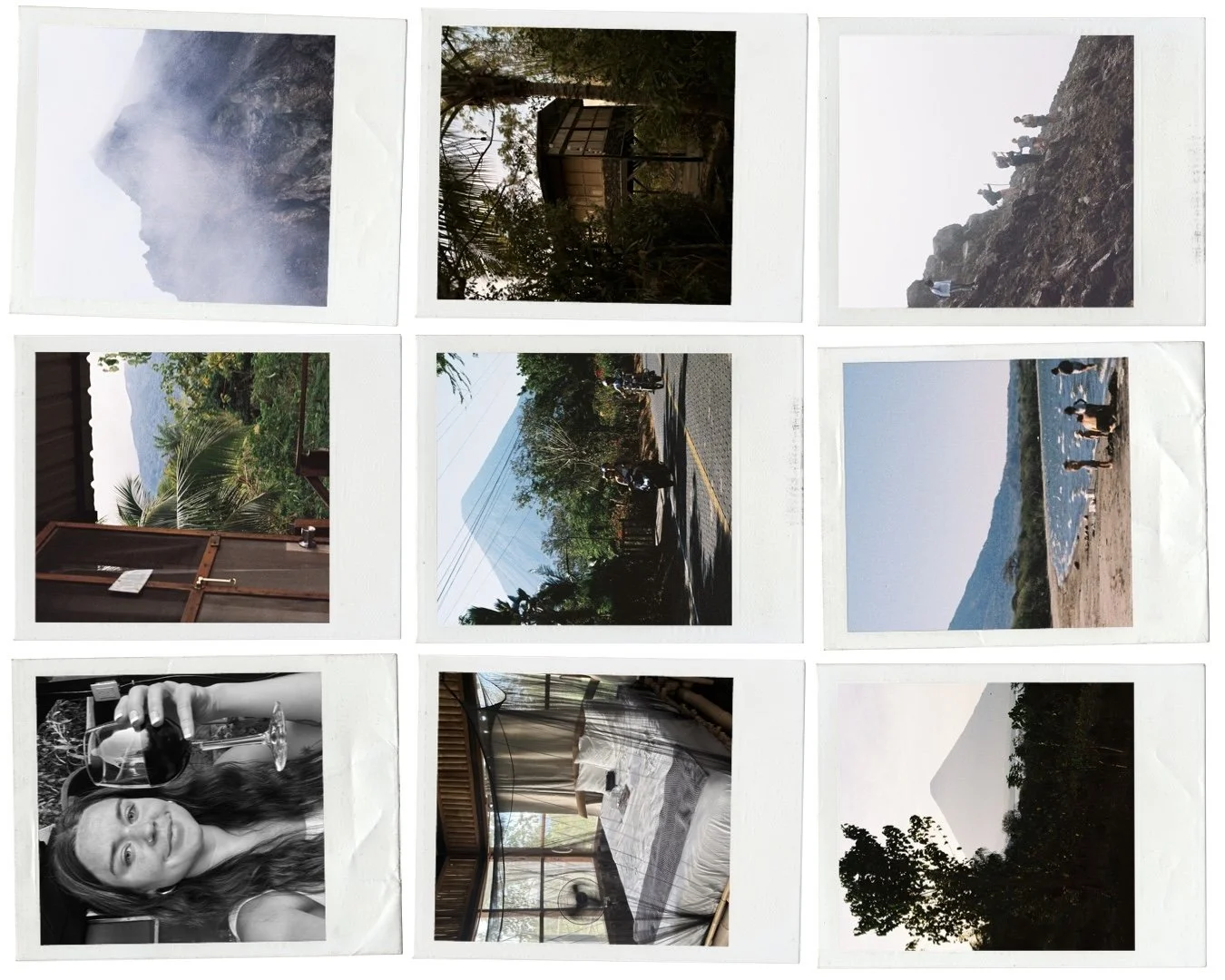

The Nicaragua Journal.

Chapter II: Ratios

Published April 15, 2024

Nicaragua has something called the Papagayo Wind. It’s integral to the country and has traveled far from where it came to get here, just like the rest of us. But I don't know this yet. All I know is that it makes everything feel dangerous.

From December to late March, it blows through the southern and eastern regions as a result of cold air moving in from North America. It breezes over the Gulf of Mexico, through a gap in the Central American Cordillera Mountains, and through Nicaragua’s Lake district. It’s responsible for mixing warm surface water with the colder waters below, which improves algae growth and provides a feeding ground that sets off a chain of critical ecological reactions. It blows offshore winds along certain coasts, giving the rare gift of a consistent break. These winds sometimes last for a few days, sometimes longer. Often, they reach hurricane speeds. While I’m around, it’s always blowing — an unwelcome travel partner that follows me everywhere I go, threatening to break me down while it helps everything around me thrive. It’s a ceaseless reminder of my strangeness.

My first night in San Juan Del Sur, it wakes me with a start around 1 am. My eyes fly open at what sounds like someone drunk, coming back from the bars in town and banging into the metal lockers in the hallway just outside of my door. Heart pounding, I see a tree whip into my window and disappear just as fast. I realize it’s the sound of branches colliding with the tin structure, but this goes on all night, keeping me on edge while my roommate sleeps soundly in the other bed. The next morning I wander a half-mile down the beach to the town center and sand pelts me so hard it’s almost painful. Now, on my first morning in Playa Maderas, one sleep removed from my initial attempt at a beach excursion, I’m sitting in my hostel’s open-air wellness studio five flights up, and the yoga teacher isn’t even trying to compete with the gusts that are shrieking all around us. I have to keep my eyes open against her instructions to get a visual of what she’s telling us to do, which she notices and hates. Every few seconds, the ends of my mat blow off the ground and into my lap, which I’m fixated on and hate. I count down the seconds until I’m bowing my head with a fabricated, “Namaste.”

The wind feels like a toddler throwing a temper tantrum, destroying all hope of peace and quiet and tossing things out of place for no good reason. In Nica, It knocks out the power every night and knocks over anything remotely flimsy that wishes to be upright, including, sometimes, me. And as every surfer knows, when it’s this unruly, it can create conflicts with the sea that we have no business getting in the middle of, which is why I leave my surf suit in my room when I head to the beach that afternoon.

When I reach the end of the path, I take out my film camera and am adjusting the focus when I hear, “Do you surf?” I glance over to find a man sitting in a foldout chair next to a rack of boards.

“Are you talking to me?”

“Si. Do you surf?”

“Yeah.”

“You’re going today.” It’s not a question.

“I don’t know about that. I need to get my eyes on the water.”

“How long have you been surfing?”

“Inconsistently for about ten years.”

“OK, so you’re surfing. What do you ride?”

“7’ 6”, usually?” I say it like it’s a question.

“I have that.”

He pulls out a white Surf Betty with giant pink Hibiscus flowers on the nose and tail. Astonishingly, it’s the same one used to I rent every summer during my teen years, before my little brother and I started accumulating our own collection of foam and fiberglass. My old diggs, the board that helped nurture my obsession, showing up for another ride more than a decade later. After a few more minutes of back and forth about the wind and conditions of the water, he finally tells me, “This is the best it’s going to be.”

“Fine. But I can’t surf in this bikini, It’s gonna fly right off. I’ll go back to my hostel, change, and come back.” He tries to argue, but I insist in a way that makes it clear he doesn’t get to argue. He asks me where I’m staying and when I tell him, he offers me a ride and walks over to his motorbike.

I’m not quick to trust people, but he somehow has my board on his rack and I have a periodic belief that there’s no such thing as a coincidence. Plus, anything I can do to avoid two more trips up and down that hill is an enthusiastic hell yes from me. I hop on without another thought and we’re back at the beach within a few minutes. He waxes my board, offers me some zinc from his backpack, and lets me store my stuff for free despite all the signs for $5 lockers posted around the beach. On my way to the water, he yells, “See you out there!” As I journey down to the sand I get smiles and high-fives from a few other locals renting boards from different racks like I’m the top contender heading out to compete in the Big Z Memorial Surf Off. I wear a huge grin as I sus out where to paddle.

Securing my spot in the lineup, I find that the water is substantially colder than it had been in Costa Rica and substantially colder than the internet said it would be. No matter. When I was sixteen I went through a phase where I refused to wear a wettie so I could tan while I surfed. There is no character building like the character building that happens when you’re a teenage girl, and it will serve me well today. Throughout the session, if I’m not paddling prematurely for mushy waves I’m keeping my hands crossed over my chest and tucked underneath my armpits for warmth. More than once, I notice that I’m the furthest out and don't know how I got there. The longer I’m in the water, the harder it’s getting to keep close to the pack and the wind starts to make the surface so choppy that I’m paddling with my eyes closed to keep them from getting blasted with salt water. I go for a few and am immediately launched off. This goes on for about an hour before I finally call it.

With blue lips and goosebumps, I fight my way down the beach, trying to angle my board to be more aerodynamic. A few times, the wind blows it perpendicular to me and I’m knocked backward, if not fully to the ground. I make it back after having to crouch down once or twice to avoid being obliterated by a few particularly husky gusts. I throw Betty back on her rack and run into a few of the board rental guys when I’m on my way back to the sand, excited to be an observer for a while. They all try to convince me to go back out. I tell them I’m only willing to tussle with one of the elements at a time. They ask me if I speak Spanish. I just laugh and say no, which is Spanish for no, and walk off with a final, “catch ya later.”

The beach is more vacant than I’m used to seeing any beach at two o’clock on a sunny day. I find a mostly empty cluster of chairs and ask the woman sitting nearby if one of them is taken. Contrary to its reputation, the social vibe at my hostel has been off-putting at best and my battery is at zero from trying so hard with people who aren’t my people, so I pull out my book, ready to lose myself in another world. One paragraph in, she asks me if I was just in the water. A conversation about outdoor sports leads to a conversation about career which leads to a conversation about relationships which leads to a conversation about values.

She and I spend a lot of time talking about what makes us happy. We talk of our strong resolve to lean into the things that do and away from the things that don’t, and we talk about how catching a moment that is fully comprised of them is rare and often not realized until it’s already over. She tells me about her brother, an incredibly accomplished mountain biker who’s since retired from competition to focus on his enjoyment of the mountains rather than his pursuit of the podium. He’s known for calling out these moments of synchronicity with the phrase, “50 to 01.” It’s a nod to the fuel-to-oil mix required for a motorbike to run smoothly, and what he’s more accurately referring to are circumstances that allow him to reach his flow state, or, “the experience of being so absorbed by an engaging, enjoyable task that your attention is completely held by it. In flow, you feel as if you could keep doing what you’re doing forever.”

These moments are what a lot of us spend our lives chasing and our respective mixtures are what a lot of us spend our lives figuring out. We do dangerous things or we set off into the unknown or we make risky decisions and, often, we endure a lot of kickback because of it. Often, we figure out a lot of what shouldn’t be in our tanks. But when it’s right, man, it’s right. When it’s right, and the ride is smooth, anything it took to get there just becomes one of the things that led you there, and that’s always worth it. We follow the pull towards our fifty-to-one moments even when we don’t know what’s waiting on the other side because the only other option is to not ride at all.

By the time the light starts to soften, I realize we’ve been chatting for nearly six hours. It’s the type of conversation that makes you eager to listen and excited to speak. Maria’s from the UK. Our lives exist an entire ocean away from each other, and they somehow happened to intersect on one tiny beach in one large country in Central America. The magnitude of this feels solid. A weight holding me down to earth, forcing me to be where my feet are, to be still long enough to look around and appreciate every detail of where I am, and be grateful for everything that led me here.

When we finally get up to leave the beach, I brush off the thick layer of sand I hadn’t noticed accumulate onto my lap, dump even more out of my tote bag, and head back up the hill.